They're Building Their Own Meat Packing Plant

✖  |

Faced with skyrocketing meat processing costs and butchers who sometimes do poor quality work, Walter Jeffries decided he couldn't afford not to build an on-farm packing house for his pigs. He already had a string of restaurants, grocery stores and other customers who wanted his pork. The only problem he had once he made the decision was he couldn't get financing to have the facility built.

"I knew I could build and equip a processing facility for about $150,000," says Jeffries. "It would pay for itself in under five years based on what we would save on custom processing."

Payback was based on eliminating average costs above and beyond processing of $114 per pig - costs associated with mistakes and poor quality processing and handling by custom slaughterhouses. On-farm slaughter would also eliminate about 37,000 miles transporting pigs off the farm and bringing pork back. Hired processing costs Jeffries $47 for every $100 earned by the farm. Doing the work themselves turns that cost into profit.

"If we do our own processing, we can more than double our net income without raising our prices or getting bigger," he says.

Unfortunately he quickly found out that positive income projections weren't enough. Banks didn't want to deal with an on-farm project, much less a slaughter facility. They especially didn't want to finance something not built by a high-priced construction company. The only answer was for the family to finance it themselves. So they did.

"We have spent about $26,000 of our own money bootstrapping the project from the base foundation on up," says Jeffries. "In addition, we have received loans from another local farmer, an excavator, a lumberyard and electric supply company for $22,000 in the form of cash, services and extended payment terms on supplies. All were appreciated and needed."

Over the past 6 mos. Jeffries, his wife, two teenage sons and a younger daughter built a 1,300 sq. ft. slaughterhouse. All engineering, concrete, plumbing and electrical work were done by the family. About the only thing they didn't do themselves was to install a bigger transformer. They also had to hire a septic system designer.

While the work started in July 2009, preparation started five years earlier as Jeffries began gathering information. When he learned in April 2008 that one, if not two, of the processors he took pigs to was going to quit, plans moved into high gear. It took 9 mos. to get the training needed to write a food safety plan. At the same time, he, his wife and oldest son apprenticed to a local butcher and began taking commercial meat cutting classes. Jeffries also began meeting with USDA and Vermont meat inspectors and anyone else whose approval he would need. He fine-tuned plans with their input and completed all the regulatory permitting required.

Along the way he learned a lot, including the importance of not breaking new ground. By building on the foundation of a 20-year old barn, he was able to move faster, such as getting zoning permission. He also found that inspectors appreciate being asked for input before work is done and credits state and federal meat inspectors with improving his plans.

"They pointed out little things, like where a sink should go, to improve my work flow," says Jeffries.

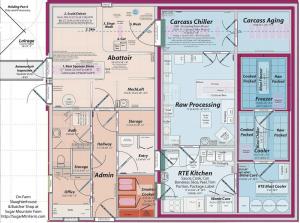

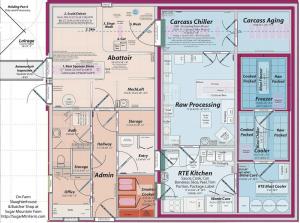

He broke the building plan up into lots of little rooms with dedicated purposes. The inspectors liked that as it makes it easier to inspect. It also made it easier for Jeffries to get his plans approved.

Plans were scaled down from older USDA plans. As it is, the new facility is built to handle up to 20 animals a day. However, Jeffries plans to do about 10 a week.

Throughout the building process, Jeffries has recycled whatever materials he could. He has also learned a great deal about cooling.

"Our goal was to stop the movement of energy across barriers," explains Jeffries. "We did that by building a large thermal mass in the concrete walls and floors to store energy with a lot of insulation to slow movement."

Jeffries built forms for the poured concrete with sheets of foam insulation that adhere to the poured concrete with sheets of foam insulation that adhere to the poured concrete. The design of the building ensures that when energy (heat or cold) does escape an area, it continues to provide benefits. For example, heat from the rooftop compressor will be channeled to rooms that would otherwise have to be heated.

The meat cutting and cooling areas, with their own poured concrete and insulation walls, are essentially a box within a box. Within that area, poured concrete freezer walls form a third box within a box. It's designed to stay at a constant 40 degrees F below zero. Cold that escapes through the floor slab under the freezer is carried by in-floor tubing to help cool surrounding areas like the processing room and the kitchen. If a door is opened in the freezer, the escaping cold air moves into the cooler, then the brine cooler and finally to the kitchen.

The septic system only handles wastes from bathrooms and the kitchen. All slaughter wastes are composted on the farm and will eventually be spread on the fields, saving waste management costs and reducing the size of the septic system that would have been needed.

When FARM SHOW spoke with Jeffries in early December, work was nearly finished. He estimated he still needed about $65,000 to get the plant equipped and running on a bare bones level.

Jeffries has kept an ongoing record of work and resources posted on his website and blog. It's full of information that would be of use to anyone considering the same type of project.

Contact: FARM SHOW Followup, Sugar Mountain Farm, LLC, 252 Riddle Pond Road, West Topsham, Vt. 05086 (ph 802 439-6462; walterj@sugarmtnfarm.com; www.sugarmtnfarm.com).

Click here to download page story appeared in.

Click here to read entire issue

They re Building Their Own Meat Packing Plant LIVESTOCK Miscellaneous Faced with skyrocketing meat processing costs and butchers who sometimes do poor quality work Walter Jeffries decided he couldn t afford not to build an on-farm packing house for his pigs He already had a string of restaurants grocery stores and other customers who wanted his pork The only problem he had once he made the decision was he couldn t get financing to have the facility built

I knew I could build and equip a processing facility for about $150 000 says Jeffries It would pay for itself in under five years based on what we would save on custom processing

Payback was based on eliminating average costs above and beyond processing of $114 per pig - costs associated with mistakes and poor quality processing and handling by custom slaughterhouses On-farm slaughter would also eliminate about 37 000 miles transporting pigs off the farm and bringing pork back Hired processing costs Jeffries $47 for every $100 earned by the farm Doing the work themselves turns that cost into profit

If we do our own processing we can more than double our net income without raising our prices or getting bigger he says

Unfortunately he quickly found out that positive income projections weren t enough Banks didn t want to deal with an on-farm project much less a slaughter facility They especially didn t want to finance something not built by a high-priced construction company The only answer was for the family to finance it themselves So they did

We have spent about $26 000 of our own money bootstrapping the project from the base foundation on up says Jeffries In addition we have received loans from another local farmer an excavator a lumberyard and electric supply company for $22 000 in the form of cash services and extended payment terms on supplies All were appreciated and needed

Over the past 6 mos Jeffries his wife two teenage sons and a younger daughter built a 1 300 sq ft slaughterhouse All engineering concrete plumbing and electrical work were done by the family About the only thing they didn t do themselves was to install a bigger transformer They also had to hire a septic system designer

While the work started in July 2009 preparation started five years earlier as Jeffries began gathering information When he learned in April 2008 that one if not two of the processors he took pigs to was going to quit plans moved into high gear It took 9 mos to get the training needed to write a food safety plan At the same time he his wife and oldest son apprenticed to a local butcher and began taking commercial meat cutting classes Jeffries also began meeting with USDA and Vermont meat inspectors and anyone else whose approval he would need He fine-tuned plans with their input and completed all the regulatory permitting required

Along the way he learned a lot including the importance of not breaking new ground By building on the foundation of a 20-year old barn he was able to move faster such as getting zoning permission He also found that inspectors appreciate being asked for input before work is done and credits state and federal meat inspectors with improving his plans

They pointed out little things like where a sink should go to improve my work flow says Jeffries

He broke the building plan up into lots of little rooms with dedicated purposes The inspectors liked that as it makes it easier to inspect It also made it easier for Jeffries to get his plans approved

Plans were scaled down from older USDA plans As it is the new facility is built to handle up to 20 animals a day However Jeffries plans to do about 10 a week

Throughout the building process Jeffries has recycled whatever materials he could He has also learned a great deal about cooling

Our goal was to stop the movement of energy across barriers explains Jeffries We did that by building a large thermal mass in the concrete walls and floors to store energy with a lot of insulation to slow movement

Jeffries built forms for the poured concrete with sheets of foam insulation that adhere to the poured concrete with sheets of foam insulation that adhere to the poured concrete The design of the building ensures that when energy heat or cold does escape an area it continues to provide benefits For example heat from the rooftop compressor will be channeled to rooms that would otherwise have to be heated

The meat cutting and cooling areas with their own poured concrete and insulation walls are essentially a box within a box Within that area poured concrete freezer walls form a third box within a box It s designed to stay at a constant 40 degrees F below zero Cold that escapes through the floor slab under the freezer is carried by in-floor tubing to help cool surrounding areas like the processing room and the kitchen If a door is opened in the freezer the escaping cold air moves into the cooler then the brine cooler and finally to the kitchen

The septic system only handles wastes from bathrooms and the kitchen All slaughter wastes are composted on the farm and will eventually be spread on the fields saving waste management costs and reducing the size of the septic system that would have been needed

When FARM SHOW spoke with Jeffries in early December work was nearly finished He estimated he still needed about $65 000 to get the plant equipped and running on a bare bones level

Jeffries has kept an ongoing record of work and resources posted on his website and blog It s full of information that would be of use to anyone considering the same type of project

Contact: FARM SHOW Followup Sugar Mountain Farm LLC 252 Riddle Pond Road West Topsham Vt 05086 ph 802 439-6462; walterj@sugarmtnfarm com; www sugarmtnfarm com

To read the rest of this story, download this issue below or click

here to register with your account number.